The Board-Staff Disconnect

21 January 2026 Leave a comment

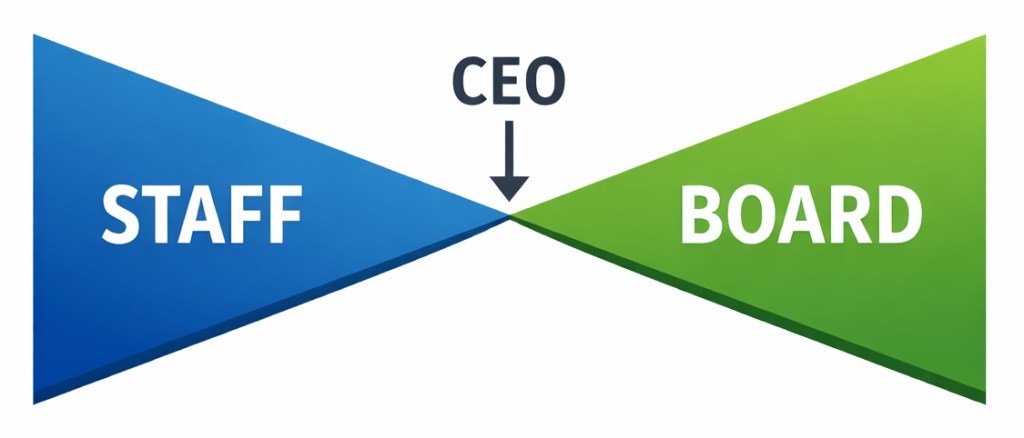

I have always viewed governance as the most critical role for the association CEO, and by governance I specifically mean the CEO’s function as the point of engagement between the board and staff.

There is an element of hierarchy to this, but org charts don’t adequately capture it. It’s a function of communication, coordination, facilitation and empowerment, to be sure. But it goes so much deeper than that. It is all about maximizing the synergy between the professional competencies unique to each side of the board/staff divide. The voluntary board and the paid professional staff each brings skills, knowledge, and expertise that the other lacks and the organization needs. The CEO alone operates in the shared space between them. The success of the enterprise lies on his/her ability to effectively engage with the board within their paradigm and engage with the staff within theirs.

Most boards recognize and respect the differences between board and staff roles. But the established way of expressing these differences, while all valid, are also insufficient. To wit:

- The board sets direction and the professional staff implements. (Sometimes the metaphor of a bicycle is used: the board is the front wheel that steers; the staff is the rear wheel that drives.)

- The CEO works for the board; all other staff work for the CEO.

- The CEO leads operations; the board provides oversight.

Like I said, none of these are actually wrong. They are all just incomplete.

And there is evidence that the gap in understanding between boards and CEOs over the effectiveness of these conceptual models is very real. Spencer Stuart released a study that asked “Do you feel the board gives the CEO effective support to address a rapidly evolving and complex business environment?” 43% of boards answered yes, but only 22% of the CEOs did. And in no universe would even the higher number be a passing grade.

So what is missing?

A recently concluded, 18-month community dialogue into the Future of Association Boards (FAB) offers some insight.

Stewardship

First and foremost: There is a missing element in most measures of performance and success. That element is an overarching and explicit commitment to stewardship.

It’s not about focusing on progress toward established goals (too often captured in strategic plans that end up being fuzzy, aspirational statements burdened with tactical “solutions” that fail to actualize them in a rapidly changing world). It’s not about a glowing “year in review” summarizing accomplishments. Even less about a chief elected officer being able to talk about the accomplishments of “his or her year in the chair.” And of course, you want to be able to do all those things authentically.

Stewardship is something more. It is about leaving the organization itself better than you found it, for the benefit of both current stakeholders and their successors in membership, on the board, and in the field.

It isn’t that a sense of stewardship has necessarily been absent. It is just that it has too often been one of those “understood” and unspoken obligations and too often taken for granted. It needs to be brought out of the shadows and made an explicit and driving force in every decision.

Foresight

The key to effective stewardship is exercising foresight: more time focusing on anticipating and understanding the next disruption that, if missed, could mean an opportunity squandered or a blow to be suffered. The American Society of Association Executive’s ForesightWorks is a rich source for understanding and framing the kinds of discussions associations should be having.

Foresight has implications for programs and initiatives, but also for the governance structures created to support them.

True Partnership

The key to making stewardship and foresight happen is a higher degree of partnership between boards and staff than exists today. And the key to making that happen starts with a clearly stated and shared commitment between the chief elected and the chief staff officer:

- With the chief elected officer accepting primary responsibility for improving board competence and performance[1] and

- The chief staff officer (and their senior management team) accepting primary responsibility for doing more than advising boards on issues within their specific functional roles, but as meaningful collaborators in the board’s exercise of stewardship and foresight.

And let me be clear: while there are ways that boards need to change[2], the accountability lies squarely on the CEO to create the means and opportunity for this happen.

Circle back to my opening thought of the CEO as the person with a foot in both the voluntary and professional staff worlds. That’s the tough assignment we all signed on for.

Disclaimer

The ideas contained here are my own. I do not speak for any organization or company.

AI was used to generate the image accompanying this post. I do NOT use AI to research, generate or edit drafts.

[1] How often can board members end their term in office feeling like the next person in the seat is joining a board better equipped to be even more effective?

[2] While we typically talk about “volunteer boards,” the FAB dialogue brought focus to the fact that while accepting service on a board is voluntary, once you have accepted that role the legal, fiduciary and ethical obligations to the organization (including stewardship and foresight) are the same as those for paid directors of for-profit corporations. That’s why an awareness of voluntary leadership’s accountability for stewardship and foresight is so important.

Although Edgar Allan Poe is most famous for his poetry and tales of the macabre, as an author he was so much more than that. The horror tales and poetry are but a tiny portion of a body of work extending to criticism of current events, literature, art, architecture and design; satire; historical fiction; proto-science fiction; travel narratives; and even serious mathematical

Although Edgar Allan Poe is most famous for his poetry and tales of the macabre, as an author he was so much more than that. The horror tales and poetry are but a tiny portion of a body of work extending to criticism of current events, literature, art, architecture and design; satire; historical fiction; proto-science fiction; travel narratives; and even serious mathematical Associations (the good ones, at least) have always served society by providing a trusted and reliable source of information. That would seem to be the key role we have to play in our current environment of decentralized information, public distrust, and AI/social media-driven echo chambers that value divisiveness and conflict over reasoned dialogue.

Associations (the good ones, at least) have always served society by providing a trusted and reliable source of information. That would seem to be the key role we have to play in our current environment of decentralized information, public distrust, and AI/social media-driven echo chambers that value divisiveness and conflict over reasoned dialogue.

Collins calls Level 5 leadership: “the paradoxical blend of personal humility and [fierce] professional will.” You need to be able to take your own ego-gratification out of the equation when assessing the association’s strategic needs, but also refuse to make allowances for any limitations that might be present on your board by compromising on the level of leadership their role demands from them. You need to be authentic in giving the board credit for association success and in truly owning any board failure as your own. And never, never, never, letting a setback cause you to doubt yourself or become tentative and risk averse. Take the hit, learn what you can from it, turn the page, and move on. In doing so, you become not only something of a safety net for the board, making it less risky for them to take bold action. You also model the behavior that will enable them to be effective in their own leadership roles.

Collins calls Level 5 leadership: “the paradoxical blend of personal humility and [fierce] professional will.” You need to be able to take your own ego-gratification out of the equation when assessing the association’s strategic needs, but also refuse to make allowances for any limitations that might be present on your board by compromising on the level of leadership their role demands from them. You need to be authentic in giving the board credit for association success and in truly owning any board failure as your own. And never, never, never, letting a setback cause you to doubt yourself or become tentative and risk averse. Take the hit, learn what you can from it, turn the page, and move on. In doing so, you become not only something of a safety net for the board, making it less risky for them to take bold action. You also model the behavior that will enable them to be effective in their own leadership roles.