The Staff > CEO > Board Relationship: A Matter of Perspective

29 January 2026 Leave a comment

Last week I wrote about the association CEO’s unique position in governance, situated as it is between professional staff and voluntary directors/leaders. That focused on the CEO’s role in advancing a culture of stewardship at both the staff and voluntary levels. I received numerous comments from CEO colleagues who agreed with everything I said but raised a slightly different and potentially more problematic set of circumstances surrounding board/staff roles. (And I heard more than one horror story about where, in their experience, things went bad, in one case to the point of nearly costing the CEO their job.)

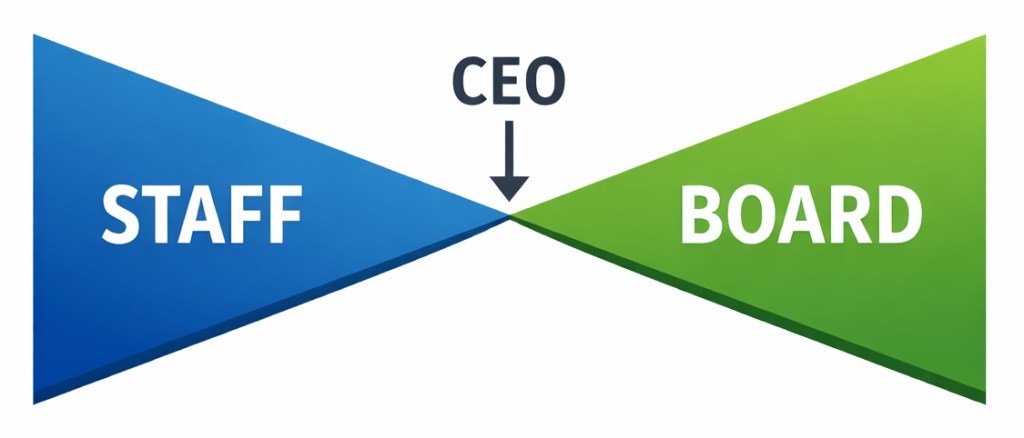

The basic principle is straightforward: the CEO is responsible to the board; all other staff are responsible to the CEO. Staff performance is itself a part of the accountability that the CEO has to the board.

Most often, all staff hiring, firing, promotion, and compensation decisions are explicitly and specifically delegated exclusively to the CEO in his/her contract. And frankly, in my own experience, I have been pretty impressed by how seriously boards have shown respect for that separation of authority. They understand why it’s so important: the board can’t hold the CEO accountable for staff performance if the board is meddling in the CEO’s autonomy to exercise the authority necessary to building and maintaining a high-performing staff.

Pretty straight forward in principle. But as my peers’ reactions to that column demonstrated, not always so clear in practice.

The Board’s Limited Perspective of Staff

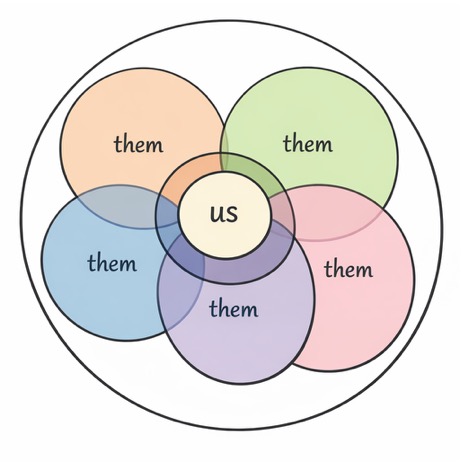

Where the challenge can arise is a matter of the board’s limited perspective of staff. Some staff positions are more member-facing than others. These are the staff members that voluntary leaders see and interact with directly. They have direct evidence of how well or how poorly such staff are performing those portions of their responsibilities that are visible to them. The problem is, they are forming a judgement based on only a limited perspective of that staff member. And they only see the pieces that touch them.

Who Goes Unnoticed?

It’s why I always get so uncomfortable when the board wants to publicly recognize a member of staff for a job well done, even when such recognition is richly deserved. Now, I am all for recognizing and celebrating individual staff everywhere and in every way that it can be done. But when the board or a committee wants to single out the director of meetings for a successful conference, or the director of credentialling for the successful launch of a new certification, or the director of government relations for a legislative win, this can potentially set off negative ramifications elsewhere in staff.

The board isn’t wrong in perceiving and wanting to acknowledge the performance of a staff member they work with directly. But they can only recognize the performance of the staff members they actually see. Who else goes unnoticed? There are always others, in less directly member-facing roles who may have contributed as much or more to the accomplishment being recognized.

There are also staff members whose roles are no less critical to the organization but are largely invisible to voluntary leaders. The only way they will ever come to the board’s attention is if something goes horribly wrong.

When any staff member who had a material role in the success the board is celebrating are left out of recognition, and whenever a staff member or department feels unrecognized, they feel demotivated, unappreciated, and marginalized.

What Aspects of Even the Staff Members They See Are Hidden from Them?

And my colleagues pointed out an even worse case but not entirely uncommon scenario. There is a staff member the board or committee works with closely and continuously over a long period of time. That staff member is exceptional in the level and quality of support they provide the board or committee. Personal relationships are built.

But they are seeing only the piece of an iceberg that is above the water.

What if there are other, legitimate performance, skill, or behavioral issues going on underneath?

Generally, these issues are minor and manageable. They might be uncomfortable and difficult for the CEO but buckle up. They can and need to be addressed. Most often, with a competent CEO, they are.

An Admittedly Extreme Example

But one particularly egregious case shared with me concerned a staff liaison who was truly extraordinary in meeting the member-facing aspects of his job. An absolute super star. But hidden from the voluntary component he supported were deeply problematic performance issues vis-à-vis this individual’s interactions with other staff. Persistent patterns of behavior that were contrary (and corrosive) to staff values and culture. And at so serious a level that other staff found ways to work around him rather than try to deal with him directly. He was that toxic an employee.

As the CEO who shared this story put it to me, she had gone to great lengths to coach and develop the employee, providing training and support and encouragement that would allow him to correct his deficiencies and be truly successful at all levels of his job. She admitted that she went above and beyond the lengths she would have gone to with a staff member in a less member-facing role. Still, the employee’s behavior truly rose to a level where dismissal was warranted. But, my CEO colleague added, “how could I fire an employee so universally beloved by every member of leadership he ever supported?”

Of course, one extreme case does not generalize to the commonplace. But it underlines the critical necessity for the CEO to cultivate a level of awareness, appreciation, and understanding by the board and other voluntary leadership that every staff member is an iceberg and they only see the piece above the water.

Building a Foundation of Trust

This is a matter of appreciating not just the principle at work but earning a solid relationship of trust by the board in the CEO’s judgement sufficient to weather the hopefully rare occasions when such a degree of trust is needed. Despite the cognitive dissonance between what the voluntary leader sees in the employee and the actions the CEO takes, do they have enough confidence in the CEO to accept on faith that he or she knows what they are doing, and that it is truly in the best interests of the organization?

As a CEO, by the time you are in the difficult situation, it is too late. Trust needs to be earned and banked before you need to rely upon it.

Disclaimer

The ideas contained here are my own. I do not speak for any organization or company.

AI was used to generate the image accompanying this post. I do NOT use AI to research, generate or edit drafts.

My association faced a challenge common to many if not all membership organizations: the imperative to diversify revenue sources and monetize our content expertise. Attacking that problem led to a shift in our business mindset.

My association faced a challenge common to many if not all membership organizations: the imperative to diversify revenue sources and monetize our content expertise. Attacking that problem led to a shift in our business mindset. Although Edgar Allan Poe is most famous for his poetry and tales of the macabre, as an author he was so much more than that. The horror tales and poetry are but a tiny portion of a body of work extending to criticism of current events, literature, art, architecture and design; satire; historical fiction; proto-science fiction; travel narratives; and even serious mathematical

Although Edgar Allan Poe is most famous for his poetry and tales of the macabre, as an author he was so much more than that. The horror tales and poetry are but a tiny portion of a body of work extending to criticism of current events, literature, art, architecture and design; satire; historical fiction; proto-science fiction; travel narratives; and even serious mathematical

Associations (the good ones, at least) have always served society by providing a trusted and reliable source of information. That would seem to be the key role we have to play in our current environment of decentralized information, public distrust, and AI/social media-driven echo chambers that value divisiveness and conflict over reasoned dialogue.

Associations (the good ones, at least) have always served society by providing a trusted and reliable source of information. That would seem to be the key role we have to play in our current environment of decentralized information, public distrust, and AI/social media-driven echo chambers that value divisiveness and conflict over reasoned dialogue.