Generations or Career Stage or Brave New World?

5 February 2026 Leave a comment

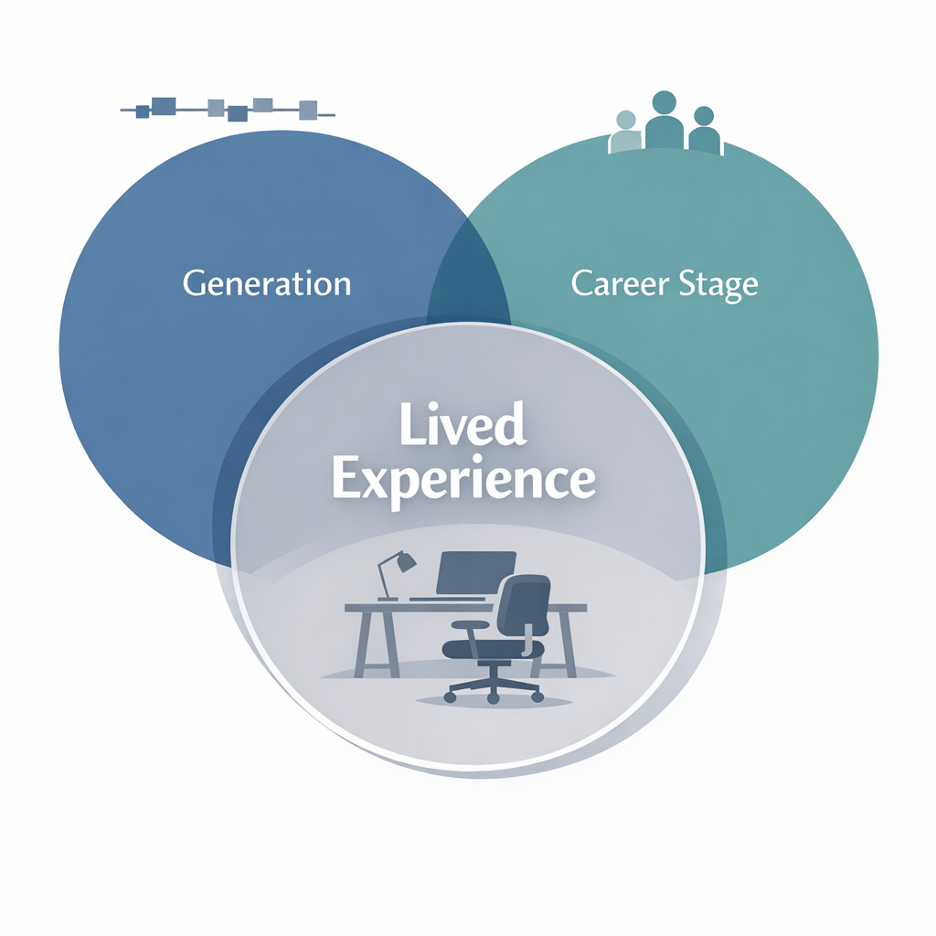

I have always been skeptical of the literature generalizing generational differences. They tend to define changes in behaviors, preferences, and attitudes based on year of birth as if these were hardwired, evolutionary changes in DNA that emerged in the species at fixed points in time. It always seemed to me that career stage (regardless of year of birth) was a far more meaningful factor in trying to understand where individuals were coming from. But I have reached the conclusion that neither are sufficient frames of reference for understanding the workforce.

I have come to appreciate the more significant impact that macro-level disrupting changes can have on all generations and levels in the workforce. How are they impacted and how do they respond to it? In short, the current lived experience is more impactful than either year of birth or career stage.

It’s about more than just technology and tools

You’ve all seen the online clickbait: “If you recognize what these pictured items are, you were definitely born before X date.” Rotary telephones, floppy disks, physical Rolodexes, etc.

But it isn’t only technology and tools that date you. At any age, you can always learn new tools. There are historic changes that affect the entire workforce even more profoundly. Epoch defining events, like world wars, economic depressions, 9/11, and the pandemic-shutdown permanently changed the world and required each of us living in it (regardless of generation) to reassess the nature of our relationship to that new world in every aspect of our lives. The workplace isn’t immune.

What constitutes normal?

It is only human nature: what we are accustomed to feels normal. Any macro event that fundamentally changes the nature of things is going to cause those used to the way things were before to feel like the new reality is abnormal. The longer the period you were able to work, grow and advance in the pre-disruption environment, the more abnormal the new world feels.

For those who never experienced what normal used to be for the role they currently find themselves in, the new normal feels like a given, even if it is a given that they are still actively struggling to grasp and understand. But it’s all new to them; they don’t have as many established habits to unlearn.

For those with work experience in their current roles both pre- and post-disruptive change, the period of uncertainty over what the rules of the road are or ought to be is equally unsettling, regardless of their generation.

The simple march of time means an increasing proportion of the working population are now digital natives. They never lived, let alone worked in a world without computers. Those who had to live through and adapt to the emergence of a digital world are increasingly, if not already a small minority. It’s probably well past time when those in this category need to just get over it. There are more pressing issues to deal with.

The post-pandemic reality

The same can’t be said for the adjustment to a post-pandemic new world. It’s still too new and too unsettled.

A small but increasing portion of the population in the workforce never worked under pre-pandemic shutdown conditions. While more seasoned workers are struggling to adopt to a “new normal,” these individuals are totally unfamiliar with the “normal” their more tenured colleagues experienced and are trying to cope with losing.

Even those who entered the workforce shortly before the pandemic lockdown have had less experience acclimating themselves to the old normal than their more seasoned co-workers. They are less hardwired into the old normal, but I don’t know if that makes resolving what the new normal ought to be easier or harder to imagine and adjust oneself to.

Maximizing flexibility is the thing we all seem to have agreed on

During a recent CEO dialogue, the usual shorthand for this topic emerged. We tend to lump this into the debate over in-person, all-virtual, or hybrid workforces. But it is more nuanced than where workers are sitting.

At least in the association space, I don’t think the 100% in-office party has built any kind of constituency.

The pro-all virtual party argues: “We worked successfully in a 100% remote work environment during the lockdown. Why does it need to change?” Assumptions about organization size correlating to success as all-virtual organizations don’t appear to hold, so judging what is most appropriate by organization size isn’t much help.

The pro-hybrid party argues that there has been a loss of social cohesion in the all-virtual environment that is costing the organization in ways that those who never experienced the pre-pandemic normal can’t fully appreciate.

No employee mourns the opportunity to jettison the cost (in time and money) of a daily commute. No CFO is upset over the opportunity to jettison high office space occupancy costs. But that doesn’t mean people aren’t frustrated when they can’t interact spontaneously and easily with others … that it’s always necessary to schedule a meet up. This is particularly true if they have lived the experience of the kind of serendipity that occurred in a staff working in close physical proximity that was taken for granted in the pre-pandemic world. (You don’t know what you’ve got ‘til it’s gone, as Joni Mitchell sang. And there … I just dated myself in a way younger gens won’t get.).

One thing is clear: whether hybrid or all-virtual, flexibility is clearly the governing value we all seem to be seeking to maximize. It enables a happier and more productive workforce.

It takes more than policy statements

But uncertainty remains the dominant state. Where does flexibility end and organizational synergy begin? Violating norms that aren’t clear to you is a source of fear, anxiety and conflicts. What is expected and what is it reasonable to expect in the desired state of maximum flexibility? It manifests itself in several specific ways.

- When is it appropriate to send an email outside of (previously) normal working hours, with the implicit expectation of response[1]?

- If my exercise of flexibility in hours worked is different than yours, what happens if our interaction is necessary?

- Is a phone call ever better than asynchronous communications and what are the norms for this?

And I could go on.

Simply writing that everyone is expected to be “available” during set, core hours into your employee manual is reasonable, but insufficient.

Similarly, mandated days in-office makes logical sense, but only if the nature of the work that occurs makes being in the office worthwhile. (And I see absolutely no logic to policies that require X days per week in the office – choose whichever days suit you. As if just being in a physical place makes magical things happen for you.)

The deeper into things you get, the more questions emerge. Second wave questions that have already emerged include such things as:

- If distant remote employees are expected to travel to HQ for mandatory all-staff events (typically between two to four times per year), who is responsible for their extraordinary travel and housing costs?

- How do workers, eager to succeed for themselves and for the organization, get the direction and support needed to be successful, beyond project plans, deadlines and tasks?

- How do (in particular) early career stage individuals build their professional networks and gain awareness of functions outside their assigned areas?

And there are trivial but amusing examples of the disconnect as well.

Like the number of employees who, in an environment of 100% remote work, asked if they would get the day off the first time a snowstorm hit.

And one colleague who got a lot of feedback that staff wanted the performance management system to be less burdensome … in a situation where employees were only asked two open-ended questions, three times per year[2].

But it goes to the issue we should have been addressing all along: how effective is our system of feedback and direction, regardless of the time required to engage in the process? And how consequential our in-office experiences actually are.

One thing seems universal: employees don’t want to follow procedures that seem to them like a waste of time. They never did. But in today’s environment, policies and procedures that don’t make the actual work experience rewarding and productive are even more toxic to the enterprise. And the evidence I have observed seems to indicate many organizations haven’t fully answered that question yet.

Where we go from here

At least four trends (or imperatives) appear to be in play:

- Clarity and shared understanding of expectations is needed in a system designed for flexibility with boundaries, communicated in a transparent and purposeful manner, not as arbitrary edicts or vague statements of the ideal, left open to interpretation.

- Better execution of virtual collaboration systems than many (most?) associations have yet to implement, even if they have the technical capacity to do so.

- Shifting to a more “results only” oversight and performance management approach, rather than time or task measurements.

- Providing coaching and development support in a separate but complementary manner.

I am encouraged by the evidence I have seen of associations that are meaningfully redesigning both the physical, in-office environment (nod to you, ASAE) and the way they organize work (both in-person or virtually). But too many associations seem to be applying Band-Aids to their pre-pandemic conditions, merely tweaking the old normal, rather than inventing the new. As a profession, we have a long way to go.

Postscript: My reference to a “brave new world” is a bit of a Rorschach test. Did it prompt dystopian dread, as in Aldous Huxley’s 1932 novel of that name? Or the utopian optimism of the Shakespeare play Huxley took the phrase from (The Tempest)? I wonder if a generational generality might be inferred from that distinction.

Disclaimer

The ideas contained here are my own. I do not speak for any organization or company.

AI was used to generate the image accompanying this post. I do NOT use AI to research, generate or edit drafts.

[1] I know the arguments both for and against “no emails after hours or on weekends.” The actual answer is, it depends.

[2] As someone who for years endured the hours long process of a Paylocity-style goal setting and performance management system, this one made me smile.

My association faced a challenge common to many if not all membership organizations: the imperative to diversify revenue sources and monetize our content expertise. Attacking that problem led to a shift in our business mindset.

My association faced a challenge common to many if not all membership organizations: the imperative to diversify revenue sources and monetize our content expertise. Attacking that problem led to a shift in our business mindset.

As NSPE ends one fiscal/program year and starts a new one, it would be typical to talk about the past year’s activity. That is worth doing: we have a good story to tell, and NSPE’s accomplishments of 2016-17 are something we can all take pride in. But that would be repeating a story that you have already been told, as it was happening.

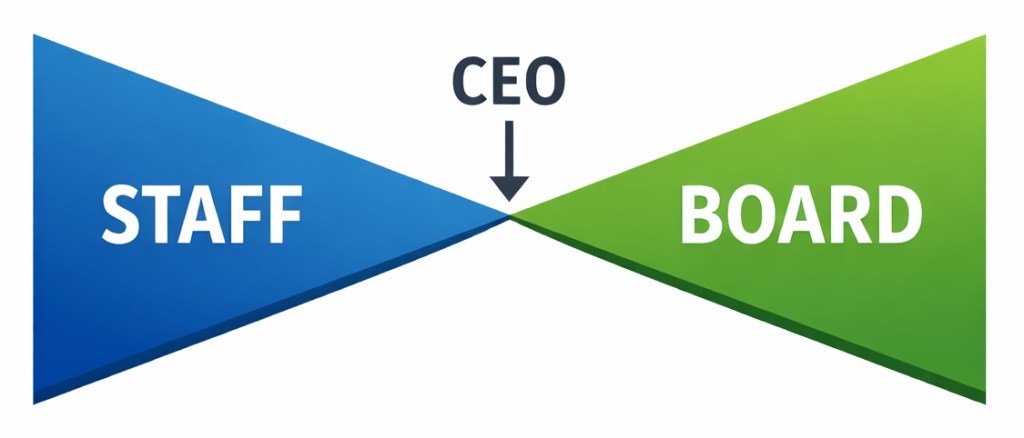

As NSPE ends one fiscal/program year and starts a new one, it would be typical to talk about the past year’s activity. That is worth doing: we have a good story to tell, and NSPE’s accomplishments of 2016-17 are something we can all take pride in. But that would be repeating a story that you have already been told, as it was happening. Collins calls Level 5 leadership: “the paradoxical blend of personal humility and [fierce] professional will.” You need to be able to take your own ego-gratification out of the equation when assessing the association’s strategic needs, but also refuse to make allowances for any limitations that might be present on your board by compromising on the level of leadership their role demands from them. You need to be authentic in giving the board credit for association success and in truly owning any board failure as your own. And never, never, never, letting a setback cause you to doubt yourself or become tentative and risk averse. Take the hit, learn what you can from it, turn the page, and move on. In doing so, you become not only something of a safety net for the board, making it less risky for them to take bold action. You also model the behavior that will enable them to be effective in their own leadership roles.

Collins calls Level 5 leadership: “the paradoxical blend of personal humility and [fierce] professional will.” You need to be able to take your own ego-gratification out of the equation when assessing the association’s strategic needs, but also refuse to make allowances for any limitations that might be present on your board by compromising on the level of leadership their role demands from them. You need to be authentic in giving the board credit for association success and in truly owning any board failure as your own. And never, never, never, letting a setback cause you to doubt yourself or become tentative and risk averse. Take the hit, learn what you can from it, turn the page, and move on. In doing so, you become not only something of a safety net for the board, making it less risky for them to take bold action. You also model the behavior that will enable them to be effective in their own leadership roles.