What does “going global” really mean?

7 January 2026 Leave a comment

It’s a question that frequently arises in conversations among my association peers. Every one of my associations has been U.S.-based but, to some degree, operated globally.[1]. And what I have learned is, like with so many questions of this kind, the answer always must start with “it depends …”

For a U.S. based association, aspiring to expand globally, I can identify at least four domains of possible activity:

Market and Revenue Enhancement

This is probably where most associations start when they are thinking about going global. What are the products or services (existing, repurposed, or new) that could be delivered outside the U.S. to generate revenue? Major caveat: there always needs to be mission consistency. Approaching international markets purely as potential ATMs for extracting revenue is not only naïve, but almost never successful. And, in my view, it is never legitimate. There needs to be a return on investment to the mission for every association offering. If it also happens to be financially lucrative, so much the better.

In some areas of the world, and depending on the scale of the program, this might require setting up overseas operations just to get in country. But not always.

Even if you are not setting up a satellite office, to be truly effective, operations in the U.S. for delivery overseas of even a single product offering requires more than just a cooperative local member in the target country. An individual member who can provide a facility to host your international event may not have the juice to attract local attendees, sponsors, and exhibitors, or the savvy to accommodate local regulatory requirements, or an understanding of what’s involved in a project of this sort. You need strong and accountable local partners, competent in the business and operational skills you aren’t present to provide directly. (And don’t get overconfident in your own ability to effectively provide marketing, sales and onsite management of operational support half way around the world.) It takes discipline to hold yourself to that requirement.

Diplomatic

Your association may be eligible for membership as the U.S. representative in an international federation. This one is tricky. In many cases the U.S. association is larger in terms of finances, scope of operations, content expertise, and staff than any other member of the federation, or even the combined resources of the federation as a whole. The federation (and its national or regional members) might value the relationship as an avenue of access to information and resources unavailable without you. But exercising your presence with too heavy a hand can cause more damage than good. (The global federation will always harbor the fear that you are after usurping their title as THE international representative of the field.)

On the other hand, if handled with diplomacy and tact, it is often very easy for your association to gain an impactful role within the federation in ways that advance your own parochial interests. Simply being more competent and experienced in association management can translate into appreciated and influential involvement.

Maintaining an actual presence and engagement in international federations is costly, both financially and in the time and attention managing the relationship consumes. Boards are often insensitive to just how much staff time and effort is consumed in ensuring that the President always gets invited to the international meeting and that we respond to every request for a “strategic alliance.”

But when budgets are tight, the question of “what are we actually getting out of this?” comes up. And the answer is often soft (and suspect): showing leadership, adding prestige. It usually comes down to FOMO.

But sometimes this is something you still need to do;

- As a show of solidarity with the profession/industry,

- To stay in the loop on what’s going on beyond U.S. borders, and

- To enhance your brand.

Being able to document specific accomplishments linked to participation is necessary.

Beyond any formal international federation, there may be opportunities for bilateral relationships with similar, usually national organizations outside the U.S. My one caveat here is: if you are going to do this, make the relationship specific, appropriately scaled, and one in which both parties get concrete value and are held accountable to each other.

Don’t fall into the MoU trap, where just having as many resolutions to frame and hang on the board room wall is your metric of success. The management time and attention necessary to maintain even this Potemkin Village of international presence can be significant.

Developmental

This is the one that personally excites me most: delivery of your association’s knowledge and expertise, directly and in service to less developed countries. I am particularly proud of one of my association’s program sending teams of members to meet with their counterparts in countries in the developing world, providing practical support in areas of professional practice and impact. We sent such missions to more than 20 countries over the course of the past decade and provided post-mission (albeit, virtual) follow up and support. This is all cost, no financial return. It is huge for the local community but can’t, by itself, move the needle globally. Yet, to the extent you can provide it, it is the truest form of global mission impact for your U.S.-based association.

Collaboration/Engagement Opportunities for your own Members and Constituents.

This one gets overlooked but can be significant. As noted above, maintaining engagement in international federations is costly. But always remember to factor in the value of the opportunities it creates for individual members to participate in activities, such as research, publication credits, speaking opportunities, committee service, etc. It may be easier for a member to get a speaking role at the federation’s comparatively smaller meeting than national’s mega-conference. (This is particularly important in fields where “publish or perish” is a career imperative.) This is also a way to identify and develop younger or early career members for future roles in the U.S. association.

The management challenge here is maintaining meaningful contact and coordination with the individuals thus engaged. They may be your association’s appointed representative on the federation’s XYZ Council, but that does neither you nor them any good if neither is aware of what the other has going on.

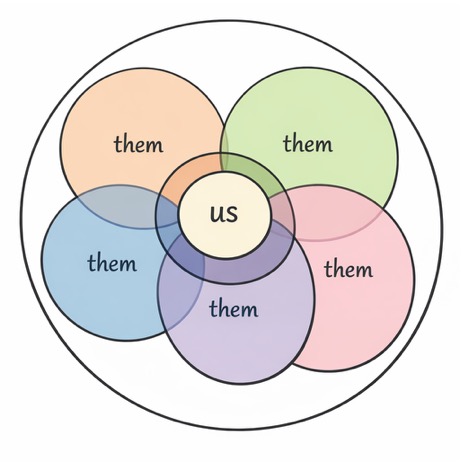

In most cases, going global involves some combination of the above. And just to keep things even more interesting, the categories sometimes bleed into each other and can sometimes come into conflict (usually, in competition for resources).

I would be interested in hearing others’ thoughts on the inventory of elements that can go into going global.

Disclaimer

The ideas contained here are my own. I do not speak for any organization or company.

AI was used to generate the image accompanying this post. I do NOT use AI to generate or edit drafts.

[1] Ironically, the presence or absence of “international” in an association’s name is not always a useful indicator of its degree of global-ness. My first association was the only one with “international” in its name, and it had the least to show for its global aspirations. My three most recent CEO gigs were with organizations that had either “national” or “American” in their names, and these had more substantive and meaningful international presence. (And in one case, this led to changing the association name to remove “American.”)

My association faced a challenge common to many if not all membership organizations: the imperative to diversify revenue sources and monetize our content expertise. Attacking that problem led to a shift in our business mindset.

My association faced a challenge common to many if not all membership organizations: the imperative to diversify revenue sources and monetize our content expertise. Attacking that problem led to a shift in our business mindset.