Politics as the Third Rail of Constructive Dialogue

18 February 2026 Leave a comment

In a recent thread on ASAE’s Collaborate discussion platform a highly (and rightfully) respected member of the community postulated a conceivable (and dire) scenario of AI’s possible long-term impact on society, citing sources which made the scenario plausible.

But here’s the thing. Plausible. Not inevitable. Intended to open a necessary dialogue, not shut it down.

Foresight Explores Possible Futures; It Doesn’t Make Predictions

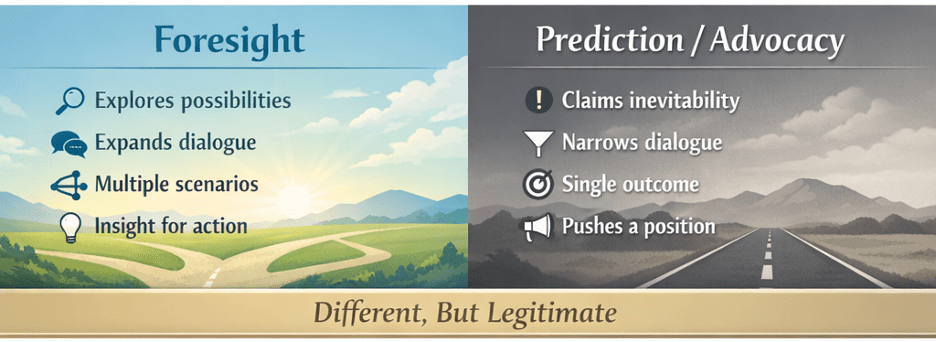

It is vital that we constantly keep in mind the distinction between exploring possible future scenarios and making predictions. Strategic planners should be doing the former, not the latter. Making predictions is a dangerous game that can lead them to shut down avenues of thought prematurely and to their long-term detriment. If their prediction is wrong, their whole strategy collapses.

Considering possible future scenarios (even the most extreme ones, positive or negative) can trigger useful strategic insights into what we need to be doing in the here and now. They don’t require us to bet the future on the likelihood of any one of a multiplicity of possible future scenarios being the one that actually plays out. They allow organizations to maintain a necessary posture of nimbleness.

Risking the Litmus Test Response

Add any hint of a political element to your scenario, and things get touchy. Any discussion of anything remotely political in today’s environment risks having your contribution attacked or (on closed platforms) even censored for being unacceptably political.

But even if tolerated, the element of politics risks something that, in my mind, is far more serious. Positing uncomfortable possible scenarios exposes you to what I call Litmus Test responses: baseless judgments made about what the scenario you shared indicates about what the reader assumes its content says about whether you are “with us or against us” politically.

Not Everyone Joins Your Conversation with the Same Intentions

Therein lies the source of the problem. When we enter into public discourse, we can approach it from a number of different postures and with a number of different purposes. It can be an exercise in foresight. Or it can be an exercise in advocacy. And the catch is, your readers might not be operating from the same posture you took in writing it.

When you engage in online discussions with the intention of stimulating an exercise in foresight, you are likely to attract responses from those less interested in strategic foresight and more interested in advancing their own (legitimate) agenda of stimulating political action.

I emphasize legitimate since such activities are certainly values-based (whether I share those values or not). And I always assume the good intentions of the poster (regardless of whether I personally agree with their agenda or not). But the purpose of this kind of public discourse is to convince. It is a strategy of reduction, not expansion. It is intended to use a scenario to move you to a particular position that supports their views and hopefully provokes political/social action and activism of a particular bent.

Like I said, legitimate. Even vital. Just different. And comingling creates misunderstanding and conflict, not understanding.

A Covert Damper on Speech?

The thing that stood out (and saddened) me most about that thread on Collaborate was the very obvious discomfort of the original poster: an individual I know to be deeply serious, well informed, qualified, and responsible. A person who had something useful to add to a discussion that could advance acting with foresight. But who was clearly concerned over how his comments might be taken or that they might get his post taken down.

It resulted in a posting that was vague and in-direct. Exactly the opposite of what is needed for an informed exercise of strategic dialogue (or activism, for that matter).

It struck me as an example of a different kind of chilling effect on the free exercise of speech. Subtle and covert, but no less unfortunate than any overt action to silence the opposition.

But I Might be Wrong

Intellectual honesty requires me to acknowledge that I am guilty of reading the Collaborate post in a manner that aligned with my own interests and purpose. But I don’t know the mind and heart of that writer. In writing this, I made the assumption that his intent was foresight. It could just as likely been intended as advocacy. Either purpose is righteous.

And either way, the concerning factor is this:

What kind of discussions are we not having because we are afraid to engage in them? And what is that costing us?

Disclaimer

The ideas contained here are my own. I do not speak for any organization or company.

AI was used to generate the image accompanying this post. I do NOT use AI to research, generate or edit drafts.

At a recent conference, I was diligent in my efforts to use social media to not only capture my own notes, but share them with my colleagues and associates, present and absent. I got a decent amount of reaction and interaction for my efforts. Retweets, likes, comments and discussion. (Nothing remotely viral, mind you, but my efforts did not go unnoticed by the (in the grand scheme of the world) relatively small community of professionals who share my interests and concerns.)

At a recent conference, I was diligent in my efforts to use social media to not only capture my own notes, but share them with my colleagues and associates, present and absent. I got a decent amount of reaction and interaction for my efforts. Retweets, likes, comments and discussion. (Nothing remotely viral, mind you, but my efforts did not go unnoticed by the (in the grand scheme of the world) relatively small community of professionals who share my interests and concerns.)